by Rebecca Bynum (August 9, 2017)

Though he served as a foreign policy advisor to the Trump campaign in 2016, Dr. Walid Phares did not join the ranks of the administration in 2017. After election-day, as he returned to the private sector, he told diplomats and journalists, who continued to seek his assessments, that he “remains at the service of the President elect and later his administration, when needed.”

Dr. Phares is a veteran when it comes to advising presidential candidates and lawmakers. Back in 2011, he was appointed as a senior national security advisor to Republican candidate Mitt Romney, who asked Phares to review the Middle East related chapter of his own book No Apology: The Case for American Greatness (March 2010) and who later endorsed the Phares’ book which predicted the Arab Spring before it happened, titled The Coming Revolution, published in October 2010.

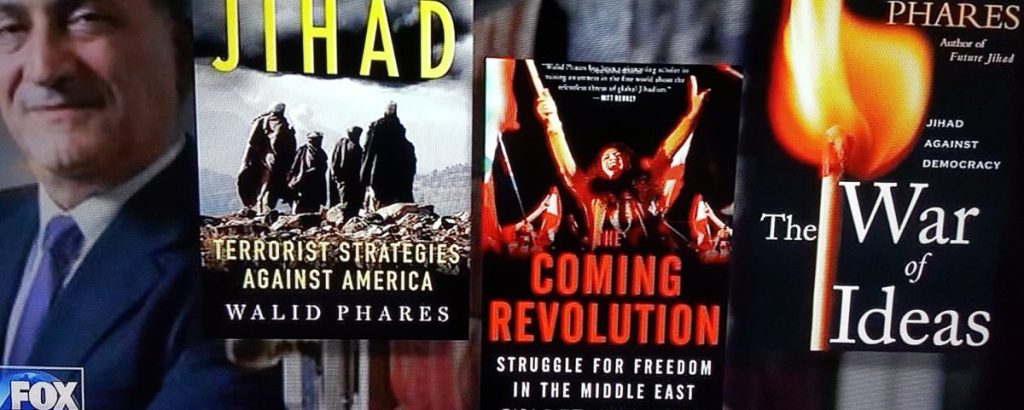

The Beirut-born scholar, who immigrated to the United States in 1990, has not only published several books and numerous articles, but has been prolific in national and international media interviews. The impact of his expertise, particularly on Jihadism, Islamism, Iran’s strategies, minorities’ issues and human rights in the Middle East, can clearly be found in number of congressional discourses, European Parliament policy conferences, the 2012 and 2016 presidential campaigns and the present administration.

Phares had briefed candidate Trump in the fall of 2015 but was not officially appointed until March 2016. Among the many talking points he advanced for the campaign on Fox News, French, British, Asian as well as Arab media was the call for an “Arab Alliance against Terror.” First published back in 2011 on al Arabiya, Phares’ concept of a NATO-like coalition was circulated in several arenas before advocated as a Trump foreign policy component in 2016. The idea, which Phares had discussed with a few Arab leaders early on, materialized when President Trump addressed fifty Arab and Muslim leaders in Riyadh earlier this year.

Another idea advanced by Phares as early as 2012, and defended during last year’s campaign, was the concept of “safe zones” in Syria. Here too, the concept was adopted by the candidate and later promoted by the president as a policy to pursue.

The notion of looking for extremist violent ideologies while countering terrorists as well as for vetting foreigners seeking to enter the United States was found years ago in Phares’ books, including Future Jihad (2005) and The War of Ideas (2007,) under the title of “Ideological Identification.” During the 2016 campaign, the foreign policy advisor filled the airwaves advocating a new sophisticated system for identifying potential Jihadi terrorists who seek to enter the United States or are already operating on the homeland.

Last but not least, another set of Phares’ ideas evolved from campaign foreign policy advocacy to a White House set of talking points. For months during 2016, Dr. Phares refuted the accusation that Donald Trump was either an “isolationist or an interventionist.” The advisor reassured European and East Asian diplomats and media, when asked, that a future President Trump would neither disband NATO nor abandon US allies. Phares’ statements in Egyptian and Gulf media were key in reassuring many partners that the next administration would rebuild lost strategic bridges.

Obviously, Walid Phares has never claimed to be an exclusive promoter of these ideas, but thick archives from 2016 and years before demonstrate how he fathered several simple concepts and defended them to the advantage of the campaign. Readers, listeners and viewers thanked him in droves for being steadfast in producing the necessary narrative to promote a new approach during the campaign as well as during the few months after the election. Walid Phares’ ingenious word-craft can be seen in his efforts to restructure a number of Donald Trump’s controversial slogans after they were publicized. One difficult theme was the candidate’s call for a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States” in December 2015. For months, Phares worked to build the argument that Trump did indeed have Muslim supporters and that his goal was to stop the Jihadists, not the religion per se, and that Trump was actually reaching deep into the Muslim world to partner against terror. These talking points helped change the international and Arab perception of the Trump image as Phares accepted dozens of interviews conducted in Arabic across the region during the campaign. Not all of the ideas advanced by the advisor ended up as part of policies, but the few that made it to the national audience, were proportionally helpful.

Another popular slogan used by candidate Trump was “America First.” It was also sharply attacked as isolationist. Brilliantly, Phares added a proposition that changed the impact of the slogan on concerned ears. In many interviews and statements as of April 2016, the foreign policy advisor told media and diplomats that “America First does not mean America Alone.” The line was not seriously noted by the campaign spokespersons until after the election. Only a few months ago, particularly after President Trump’s visit to Europe and his speech to NATO, did White House advisors begin to use the phrase in defense of the President’s standing worldwide.

Walid Phares’ contribution may not have been referred to by the users of the slogan, but what counts for the scholar in world affairs is the contribution to the public cause, that is, to defend America as a powerful, credible and compassionate superpower.

Although Dr. Walid Phares may not have landed a job in the Cabinet or White House this year, there is no doubt—as a long trail of references show—his ideas have certainly landed in the White House narrative.

First published in New English Review.